Eurasian Eagle-Owl, Celebrity Bird Mythology

When I first started watching Pale Male and the Red-tailed Hawk nest at 927 Fifth Avenue in 2005, I had my first experience with a celebrity bird. I learned then that the public perception of Pale Male didn’t match his reality. Rather than observing Pale Male people wanted to repeat back what they had learned from Marie Winn’s book, Red-tails in Love or Frederic Lilien’s movies, Pale Male and The Legend of Pale Male.

I would observe Pale Male in Central Park’s Ramble drinking water and taking a bath and then walk to the “hawk bench”, which had a great view of 927 Fifth Avenue and the nearby buildings. When I would relay this information to Pale Male fans, I would often have people question my observations. Generally, these were people who only came to watch Pale Male a few weeks a year, and only from the hawk bench. They would say “hawks don’t drink water”. Hawks, especially eyasses on the nest, can get all the water they need from their food, but once off the nest, if given a chance they will drink water. But a group of folks had taken this to mean they don’t drink water at all, and believed it to gospel.

This happened with lots of other observation as well. It always frustrated me because I thought the greatest joy of watching Pale Male and his family was that we got to make direct observations year round of species and learn more than was ever possible just reading. Watching him was so great because every day was different, and I saw things I had never read about in books. For example, If a newly fledged offspring was being mobbed, Pale Male would come in and get the jays to go after him. Or how each year, he would hunt around the Alexander Hamilton statue in the fall after the apples began to fall as it attracted rodents. Or how he would be out of sight, but if his mate called for him to relieve her on the nest, he would quickly arrive and often have food.

These direct observations, and sharing and debating their meaning with others in person, was the joy of watching Pale Male.

I also learned early on that the folks crafting him public image, had a vested interest in molding his image. I created this blog, because Marie Winn who I had been sharing photographs for her Central Park Nature News website, refused to publish a wonderful series of photograph of Pale Male eating a Brown Rat. She said to me, “these pictures would upset my audience”. It was a nice lesson to learn. That folks who rode the coattails of a celebrity bird had a vested interest to only report the “bright side”.

Sadly, this “bright side” distortion and a failure of the general public to question the reporting, is occurring today. It is even worse now that the communications have shifted from blogs to social media.

When I got back from California in late November, I ran into a number that of people who said the reason Flaco left Central Park was because of crows and hawk. Of the any number of reasons Flaco left the park, this is low on the list.

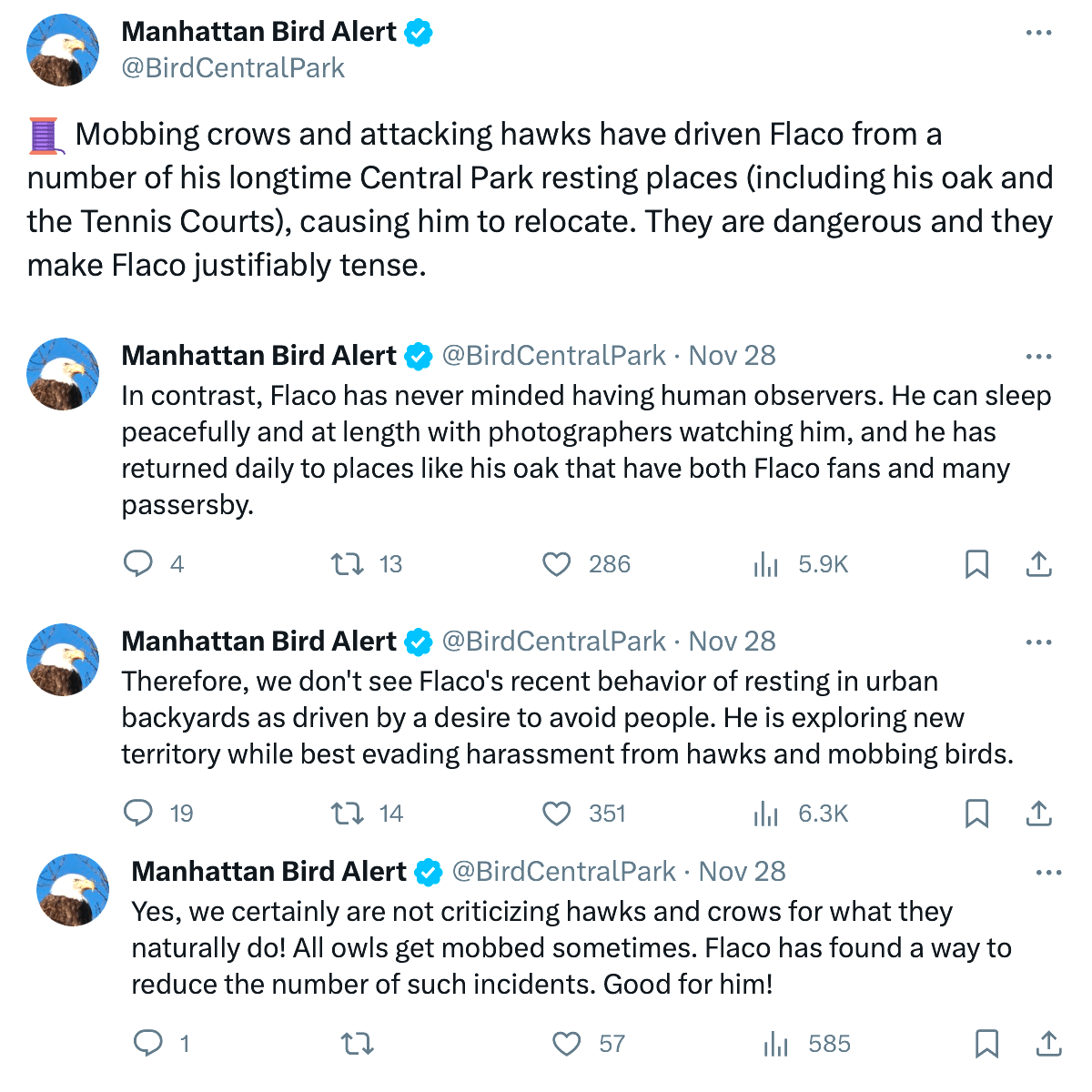

I asked folks, why they thought this and they said they had read it on the Manhattan Bird alert. So, I looked at X. This is the set of posts from David Barrett.

I believe Mr. Barrett crafted a response to answer criticism of his reporting the roost locations of Flaco in the North Woods, rather than giving a scientifically based answer. I was in California on the two days Flaco returned to the park, but many experienced birders felt the crowds on both days bothered him, and might have contributed to his leaving the park again.

So, I’d like to give an alternative perspective.

- Flaco was harassed by many birds during his nine months of roosting in Central Park. Crows, Blue Jays, Red-tailed Hawks, Baltimore Orioles and Northern Mockingbirds among others. It was a daily occurrence, and quite natural. Flaco held his own in the face of these attacks. I doubt these attacks were ever the reason he shifted roosts. He’s an apex predator!

As far as the Tennis Court roosts go, I think most of us who watched him during that period, saw Flaco be very aggressive with a Red-tailed Hawk who was working to claim the area. In the end, Flaco drove the hawk away, and once he did he returned to his preferred American Elm. So, it is more likely that Flaco forced the Red-tailed Hawk to relocate then the other way around. - Flaco did and does get disturbed by human observers. David’s statement that he doesn’t is false. It’s common sense that birds and animals get disturbed by human observers. Everyone knows this. Birders work hard to minimize their impact. With owls it is common practice not to share their roosting locations publicly to protect the owls from being disturbed during the day. All of the true bird alerts run by the NYC community (rather than David Barrett’s self run Manhattan Bird Alert), have rules against reporting owl roost locations. (And why does Mr. Barrett use the royal “we”?)

While it was possible to watch Flaco without disturbing him, there were many inexperienced or very aggressive owl watchers who did disturb him. You would see him be awoken midday and see his change in body posture. He also hated the off leash dogs people brought under his roosts. There was even a time where an observer took a stick to wake Flaco up so he could photograph him awake.

Flaco’s returning to a roost location day after day, or any owl (such the Saw-whet Owl in Shakespeare Garden, Geraldine (Great Horned Owl) or Barry (Barred Owl) shouldn’t be used as a way to justify publicizing a roost location. Rationalizing irresponsible behavior by saying “Well if the owl didn’t like people, they would move”, doesn’t cut it. I doubt the subject of roost location has been studied well enough to determine the instinctual reasons why birds choose a specific roost and what makes them abandon a location. - Why Flaco left the park most likely isn’t because he was being mobbed. If it really bothered him, he would have left months ago. There were a great number of factors to consider about why he left the park.

a. As the days got shorter, a male Eurasian Eagle-Owl would become more focused on securing his territory, investigating to see if there was a competitor nearby, and looking for an appropriate nesting location. Early November was the perfect time for these instincts to be awakened in Flaco. His looking for a mate would start a bit later. Central Park doesn’t have a suitable nest location for Flaco.

Eurasian Eagle-Owls don’t build nests. They use cliffs, take over other raptor nests, and in some very rural locations nest on the ground. In European cities, they have nested on Cathedrals and in one case even used someone’s flower box.

So, after Flaco discovered quiet gardens and the backs of buildings to roost on during his first trip away from the park, and after coming back for two days with his regular roosts surrounded by noisy people and being mobbed by birds, he may have realized his best options was to roost in a quiet block, but still stay close to Central Park where he can still hunt. Many of us hope that he continues to roost near Central Park, and then hunt in the park, where the rodents are less likely to have rodenticide.

But since Flaco is an exception to the rule, it is hard to know what he’s doing. Will he take longer trips away, say to other areas of Manhattan, when it is closer to his time to mate? We just have to wait and see.

b. The trees were just starting to lose their leaves when Flaco left, and by now his regular root trees are bare. This could have made the park less attractive than it was this summer. (Update 12/20/23: Another factor may be the windy weather. Flaco has been roosting in light wells on the back of buildings on both the Upper East and Upper West Sides. These might be giving him protection from the wind and be warmer as the temperatures drop rather than roosting in a tree without leaves.)

c. As Flaco becomes more used to his environment, he should start behaving more and more like a wild Eurasian Eagle-Owl rather than a feral bird. Central Park is 3.41 km2 and Manhattan is 59 km2 in size. Scientific studies about Eurasian Eagle-Owl territory sizes are limited but the Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity has an excellent open access paper, Analysis of Home Range of Eurasian Eagle Owl (Bubo bubo) by WT-100. The home ranges varied from 4.2 km2 to 39.1 km2 for the owls studied in the paper. So, we should have expected Flaco to expand his range beyond Central Park’s 3.41 km2. There didn’t need to be any reason he left Central Park, other than it was a smaller territory than would have been natural for an Eurasian Eagle-Owl.

Flaco is becoming much harder to find these days. His was seen just inside the park on Saturday night, and was seen the previous two Saturday’s along Central Park West. He has gone undetected on many days. When and if he returns to roosting in the park, we should take care not to love him too much.