Upper West Side IX

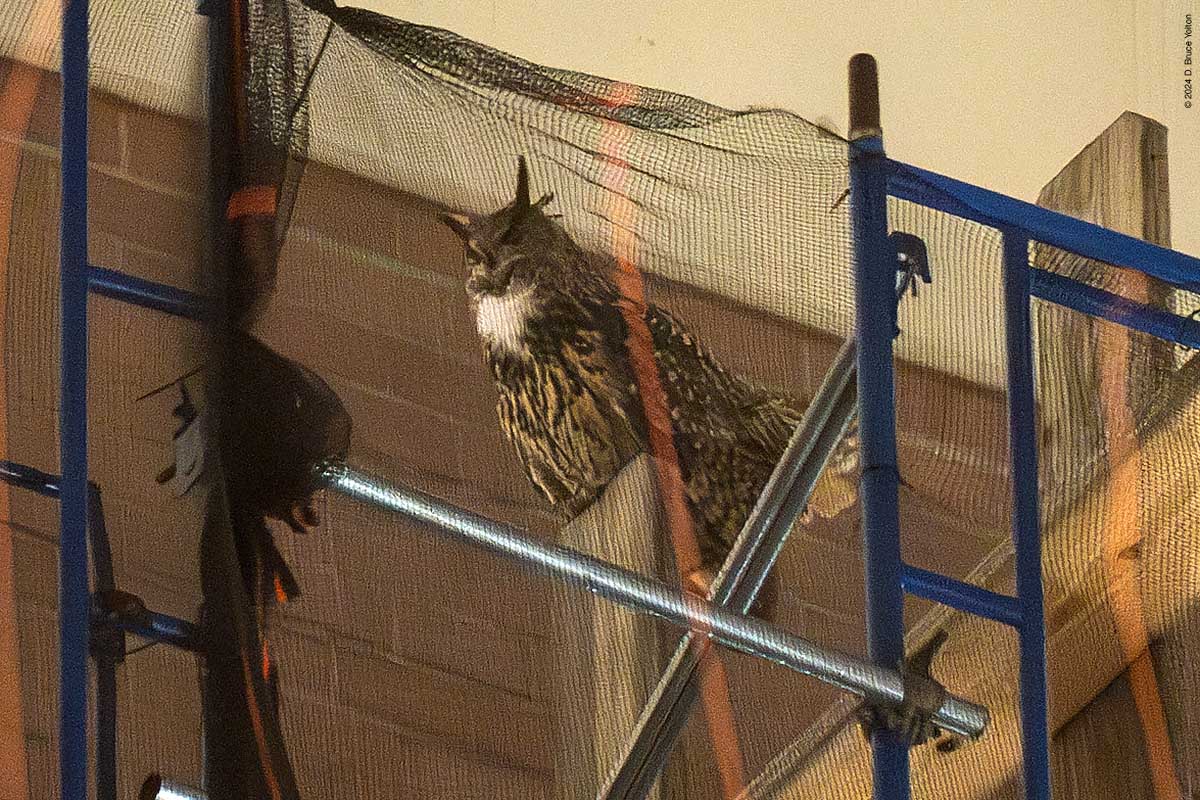

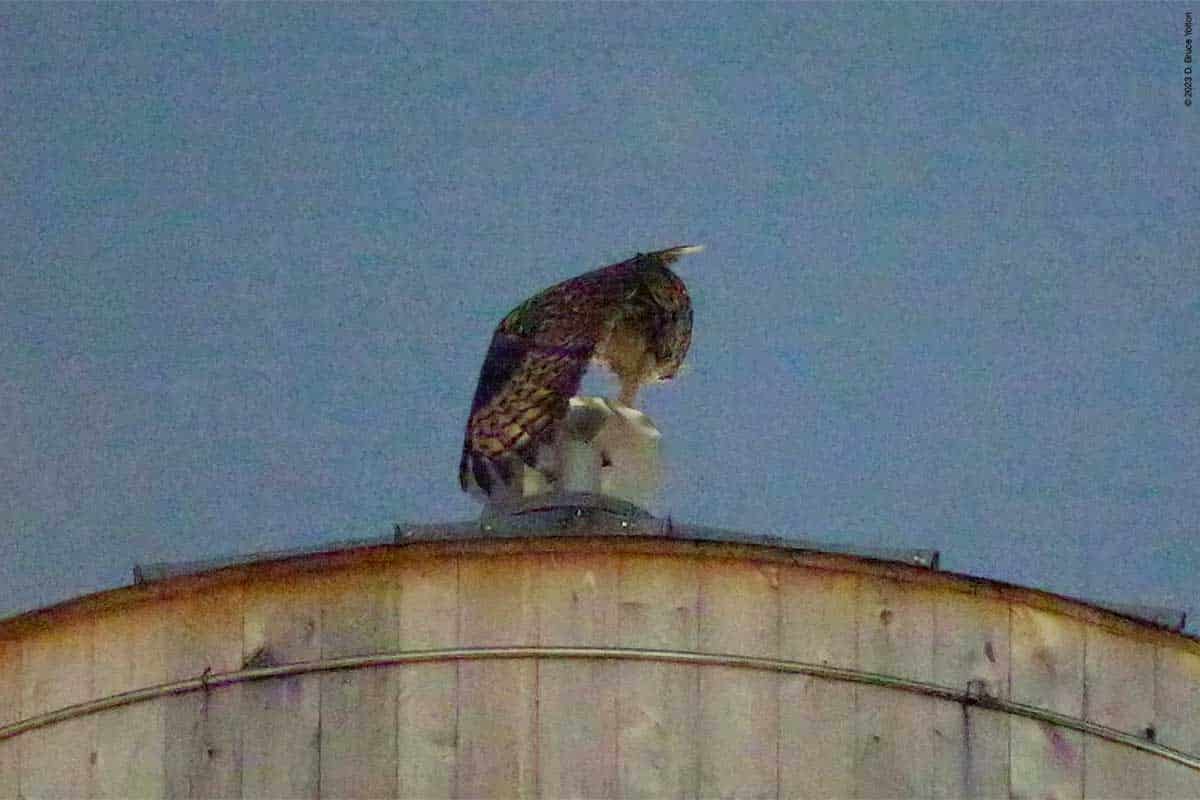

I arrived after having dinner with friends to hear Flaco from West End Avenue around 88th Street. I couldn’t find him, as his sound echos making it hard to find him, but I did see him fly out towards 90th Street. He hooted for hours from 250 West 90th, using three locations on the building. My video from the night is short. The street noise from Broadway and the questions from many curious New Yorkers, made if difficult to record him hooting.